Butyric acid (from Greek βοÏÏ„á¿¡Ïον, meaning "butter"), also known under the systematic name butanoic acid, abbreviated BTA, is a carboxylic acid with the structural formula CH3CH2CH2-COOH. Salts and esters of butyric acid are known as butyrates or butanoates. Butyric acid is found in milk, especially goat, sheep and buffalo milk, butter, Parmesan cheese, and as a product of anaerobic fermentation (including in the colon and as body odor). It has an unpleasant smell and acrid taste, with a sweetish aftertaste (similar to ether). It can be detected by mammals with good scent detection abilities (such as dogs) at 10 ppb, whereas humans can detect it in concentrations above 10 ppm.

Butyric acid is present in, and is the main distinctive smell of, human vomit.

Butyric acid was first observed (in impure form) in 1814 by the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. By 1818, he had purified it sufficiently to characterize it. The name of butyric acid comes from the Latin word for butter, butyrum (or buturum), the substance in which butyric acid was first found.

Chemistry

Butyric acid is a fatty acid occurring in the form of esters in animal fats. The triglyceride of butyric acid makes up 3% to 4% of butter. When butter goes rancid, butyric acid is liberated from the glyceride by hydrolysis, leading to the unpleasant odor. It is an important member of the fatty acid subgroup called short-chain fatty acids. Butyric acid is a medium-strong acid that reacts with bases and strong oxidants, and attacks many metals.

The acid is an oily, colorless liquid that is easily soluble in water, ethanol, and ether, and can be separated from an aqueous phase by saturation with salts such as calcium chloride. It is oxidized to carbon dioxide and acetic acid using potassium dichromate and sulfuric acid, while alkaline potassium permanganate oxidizes it to carbon dioxide. The calcium salt, Ca(C4H7O2)2·H2O, is less soluble in hot water than in cold.

Butyric acid has a structural isomer called isobutyric acid (2-methylpropanoic acid).

Production

It is industrially prepared by the fermentation of sugar or starch, brought about by the addition of putrefying cheese, with calcium carbonate added to neutralize the acids formed in the process. The butyric fermentation of starch is aided by the direct addition of Bacillus subtilis. Salts and esters of the acid are called butyrates or butanoates.

Butyric acid or fermentation butyric acid is also found as a hexyl ester hexyl butyrate in the oil of Heracleum giganteum (a type of hogweed) and as the octyl ester octyl butyrate in parsnip (Pastinaca sativa); it has also been noticed in skin flora and perspiration.

Uses

Butyric acid is used in the preparation of various butyrate esters. Low-molecular-weight esters of butyric acid, such as methyl butyrate, have mostly pleasant aromas or tastes. As a consequence, they find use as food and perfume additives. It is also used as an animal feed supplement, due to the ability to reduce pathogenic bacterial colonization. It is an approved food flavoring in the EU FLAVIS database (number 08.005).

Due to its powerful odor, it has also been used as a fishing bait additive. Many of the commercially available flavors used in carp (Cyprinus carpio) baits use butyric acid as their ester base; however, it is not clear whether fish are attracted by the butyric acid itself or the substances added to it. Butyric acid was, however, one of the few organic acids shown to be palatable for both tench and bitterling.

The substance has also been used as a stink bomb by Sea Shepherd Conservation Society to disrupt Japanese whaling crews, as well as by anti-abortion protesters to disrupt abortion clinics.

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

Butyrate is produced as end-product of a fermentation process solely performed by obligate anaerobic bacteria. Fermented Kombucha "tea" includes butyric acid as a result of the fermentation. This fermentation pathway was discovered by Louis Pasteur in 1861. Examples of butyrate-producing species of bacteria:

- Clostridium butyricum

- Clostridium kluyveri

- Clostridium pasteurianum

- Fusobacterium nucleatum

- Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens

- Eubacterium limosum

The pathway starts with the glycolytic cleavage of glucose to two molecules of pyruvate, as happens in most organisms. Pyruvate is then oxidized into acetyl coenzyme A using a unique mechanism that involves an enzyme system called pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase. Two molecules of carbon dioxide (CO2) and two molecules of elemental hydrogen (H2) are formed as waste products from the cell. Then,

ATP is produced, as can be seen, in the last step of the fermentation. Three molecules of ATP are produced for each glucose molecule, a relatively high yield. The balanced equation for this fermentation is

- C6H12O6 â†' C4H8O2 + 2 CO2 + 2 H2.

Several species form acetone and n-butanol in an alternative pathway, which starts as butyrate fermentation. Some of these species are:

- Clostridium acetobutylicum, the most prominent acetone and propianol producer, used also in industry

- Clostridium beijerinckii

- Clostridium tetanomorphum

- Clostridium aurantibutyricum

These bacteria begin with butyrate fermentation, as described above, but, when the pH drops below 5, they switch into butanol and acetone production to prevent further lowering of the pH. Two molecules of butanol are formed for each molecule of acetone.

The change in the pathway occurs after acetoacetyl CoA formation. This intermediate then takes two possible pathways:

- acetoacetyl CoA â†' acetoacetate â†' acetone

- acetoacetyl CoA â†' butyryl CoA â†' butyraldehyde â†' butanol

Highly-fermentable fiber residues, such as those from resistant starch, oat bran, pectin, and guar are transformed by colonic bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) including butyrate, producing more SCFA than less fermentable fibers such as celluloses. One study found that resistant starch consistently produces more butyrate than other types of dietary fiber. The production of SCFA from fibers in ruminant animals such as cattle is responsible for the butyrate content of milk and butter.

Cancer

The role of butyrate differs between normal and cancerous cells. This is known as the "butyrate paradox". Butyrate inhibits colonic tumor cells, and promotes healthy colonic epithelial cells; but the signaling mechanism is not well understood. A review suggested the chemopreventive benefits of butyrate depend in part on amount, time of exposure with respect to the tumorigenic process, and the type of fat in the diet. The production of volatile fatty acids such as butyrate from fermentable fibers may contribute to the role of dietary fiber in colon cancer.

Butyric acid can act as an HDAC inhibitor, inhibiting the function of histone deacetylase enzymes, thereby favoring an acetylated state of histones in the cell. Acetylated histones have a lower affinity for DNA than nonacetylated histones, due to the neutralization of electrostatic charge interactions. In general, it is thought that transcription factors will be unable to access regions where histones are tightly associated with DNA (i.e., nonacetylated, e.g., heterochromatin). Therefore, butyric acid is thought to enhance the transcriptional activity at promoters, which are typically silenced or downregulated due to histone deacetylase activity.

Two HDAC inhibitors, sodium butyrate (NaB) and trichostatin A (TSA), increase lifespan in experimental animals.

Butyrate is a major metabolite in colonic lumen arising from bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber and has been shown to be a critical mediator of the colonic inflammatory response. Butyrate possesses both preventive and therapeutic potential to counteract inflammation-mediated ulcerative colitis (UC) and colorectal cancer. One mechanism underlying butyrate function in suppression of colonic inflammation is inhibition of the IFN-γ/STAT1 signaling pathways at least partially through acting as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. While transient IFN-γ signaling is generally associated with normal host immune response, chronic IFN-γ signaling is often associated with chronic inflammation. It has been shown that Butyrate inhibits activity of HDAC1 that is bound to the Fas gene promoter in T cells, resulting in hyperacetylation of the Fas promoter and up-regulation of Fas receptor on the T cell surface. It is thus suggested that Butyrate enhances apoptosis of T cells in the colonic tissue and thereby eliminates the source of inflammation (IFN-γ production).

Safety

The United States Environmental Protection Agency rates and regulates butyric acid as a toxic substance.

Personal protective equipment such as rubber or PVC gloves, protective eye goggles, and chemical-resistant clothing and shoes are used to minimize risks when handling butyric acid.

Inhalation of butyric acid may result in soreness of throat, coughing, a burning sensation and laboured breathing. Ingestion of the acid may result in abdominal pain, shock, and collapse. Physical exposure to the acid may result in pain, blistering and skin burns, while exposure to the eyes may result in pain, severe deep burns and loss of vision.

See also

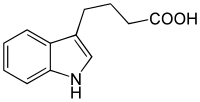

- Indole-3-butyric acid

- Acids in wine

- Gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.Â

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 1334

- 2004 review of the scientific evidence on butanoate/butyrate vs. colon cancer

0 komentar :

Posting Komentar