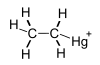

Methylmercury (sometimes methyl mercury) is an organometallic cation with the formula [CH3Hg]+. It is a bioaccumulative environmental toxicant.

Structure

"Methylmercury" is a shorthand for "monomethylmercury", and is more correctly "monomethylmercury(II) cation". It is composed of a methyl group (CH3-) bonded to a mercury ion; its chemical formula is CH3Hg+ (sometimes written as MeHg+). Has a positively charged ion it readily combines with anions such as chloride (Clâˆ'), hydroxide (OHâˆ') and nitrate (NO3âˆ'). It also has very high affinity for sulfur-containing anions, particularly the thiol (-SH) groups on the amino acid cysteine and hence in proteins containing cysteine, forming a covalent bond. More than one cysteine moiety may coordinate with methylmercury, and methylmercury may migrate to other metal-binding sites in proteins.

Sources of methylmercury

Environmental sources

In the past, methylmercury was produced directly and indirectly as part of several industrial processes such as the manufacture of acetaldehyde. Currently there are few anthropogenic sources of methylmercury pollution other than as an indirect consequence of the burning of wastes containing inorganic mercury and from the burning of fossil fuels, particularly coal. Although inorganic mercury is only a trace constituent of such fuels, their large scale combustion in utility and commercial/industrial boilers in the United States alone results in release of some 80.2 tons (73 tonnes) of elemental mercury to the atmosphere each year, out of total anthropogenic mercury emissions in the United States of 158 tons (144 tonnes)/year. Natural sources of mercury to the atmosphere include volcanoes, forest fires, volatization from the ocean and weathering of mercury-bearing rocks.

Methylmercury is formed from inorganic mercury by the action of anaerobic organisms that live in aquatic systems including lakes, rivers, wetlands, sediments, soils and the open ocean. This methylation process converts inorganic mercury to methylmercury in the natural environment. Acute methylmercury poisoning occurred at Grassy Narrows in Ontario, Canada (see Ontario Minamata disease) as a result of mercury released from the mercury-cell Chloralkali process, which uses liquid mercury as an electrode in a process that entails electrolytic decomposition of brine, followed by mercury methylation in the aquatic environment.

An acute methylmercury poisoning tragedy occurred in Minamata, Japan following release of methylmercury into Minamata Bay and its tributaries (see Minamata disease). In the Ontario case, inorganic mercury discharged into the environment was methylated in the environment; whereas in Minamata, Japan, there was direct industrial discharge of methylmercury.

Dietary sources

Because methylmercury is formed in aquatic systems and because it is not readily eliminated from organisms it is biomagnified in aquatic food chains from bacteria, to plankton, through macroinvertebrates, to herbivorous fish and to piscivorous (fish-eating) fish. At each step in the food chain, the concentration of methylmercury in the organism increases. The concentration of methylmercury in the top level aquatic predators can reach a level a million times higher than the level in the water. This is because methylmercury has a half-life of about 72 days in aquatic organisms resulting in its bioaccumulation within these food chains. Organisms, including humans, fish-eating birds, and fish-eating mammals such as otters and whales that consume fish from the top of the aquatic food chain receive the methylmercury that has accumulated through this process. Fish and other aquatic species are the only significant source of human methylmercury exposure.

The concentration of mercury in any given fish depends on the species of fish, the age and size of the fish and the type of water body in which it is found. In general, fish-eating fish such as shark, swordfish, marlin, larger species of tuna, walleye, largemouth bass, and northern pike, have higher levels of methylmercury than herbivorous fish or smaller fish such as tilapia and herring. Within a given species of fish, older and larger fish have higher levels of methylmercury than smaller fish. Fish that develop in water bodies that are more acidic also tend to have higher levels of methylmercury.

Biological impact

Human health effects

Ingested methylmercury is readily and completely absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract. It is mostly found complexed with free cysteine and with proteins and peptides containing that amino acid. The methylmercuric-cysteinyl complex is recognized by amino acid transporting proteins in the body as methionine, another essential amino acid. Because of this mimicry, it is transported freely throughout the body including across the bloodâ€"brain barrier and across the placenta, where it is absorbed by the developing fetus. Also for this reason as well as its strong binding to proteins, methylmercury is not readily eliminated. Methylmercury has a half-life in human blood of about 50 days.

Several studies indicate that methylmercury is linked to subtle developmental deficits in children exposed in-utero such as loss of IQ points, and decreased performance in tests of language skills, memory function and attention deficits. Methylmercury exposure in adults has also been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease including heart attack. Some evidence also suggests that methylmercury can cause autoimmune effects in sensitive individuals. Despite some concerns about the relationship between methylmercury exposure and autism, there are few data that support such a link. Although there is no doubt that methylmercury is toxic in several respects, including through exposure of the developing fetus, there is still some controversy as to the levels of methylmercury in the diet that can result in adverse effects. Recent evidence suggests that the developmental and cardiovascular toxicity of methylmercury may be mediated by co-exposures to omega-3 fatty acids and perhaps selenium, both found in fish and elsewhere

There have been several episodes in which large numbers of people were severely poisoned by food contaminated with high levels of methylmercury, notably the dumping of industrial waste that resulted in the pollution and subsequent mass poisoning in Minamata and Niigata, Japan and the situation in Iraq in the 1960s and 1970s in which wheat treated with methylmercury as a preservative and intended as seed grain was fed to animals and directly consumed by people (see Basra poison grain disaster). These episodes resulted in neurological symptoms including paresthesias, loss of physical coordination, difficulty in speech, narrowing of the visual field, hearing impairment, blindness, and death. Children who had been exposed in-utero through their mothers' ingestion were also affected with a range of symptoms including motor difficulties, sensory problems and mental retardation.

At present, exposures of this magnitude are rarely seen and are confined to isolated incidents. Accordingly, concern over methylmercury pollution is currently focused on more subtle effects that may be linked to levels of exposure presently seen in populations with high to moderate levels of dietary fish consumption. These effects are not necessarily identifiable on an individual level or may not be uniquely recognizable as due to methylmercury. However, such effects may be detected by comparing populations with different levels of exposure. There are isolated reports of various clinical health effects in individuals who consume large amounts of fish; however, the specific health effects and exposure patterns have not been verified with larger, controlled studies.

Many governmental agencies, the most notable ones being the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Health Canada, and the European Union Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General, as well as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), have issued guidance for fish consumers that is designed to limit methylmercury exposure from fish consumption. At present, most of this guidance is based on protection of the developing fetus; future guidance, however, may also address cardiovascular risk. In general, fish consumption advice attempts to convey the message that fish is a good source of nutrition and has significant health benefits, but that consumers, in particular pregnant women, women of child-bearing age, nursing mothers, and young children, should avoid fish with high levels of methylmercury, limit their intake of fish with moderate levels of methylmercury, and consume fish with low levels of methylmercury no more than twice a week.

Effects on fish and wildlife

In recent years, there has been increasing recognition that methylmercury affects fish and wildlife health, both in acutely polluted ecosystems and ecosystems with modest methylmercury levels. Two reviews document numerous studies of diminished reproductive success of both fish, fish-eating birds, and mammals due to methylmercury contamination in aquatic ecosystems. A study by U.S. researcher Peter Frederick suggests methylmercury may increase male homosexuality in birds: Except a control group, all of 160 captured young ibises were given small amounts of methylmercury with their food. The reproductive behaviour of these coastal wading birds changed in such a way, that the more methylmercury was ingested the more male birds choose to build nests with other males, and snub females. However, the building of nests with other males does not necessarily point to "homosexual" behavior, but rather non-sexual psychological disorder.

In public policy

Methylmercury contamination in fish, along with fish consumption advisories, has the potential to disrupt people's eating habits, fishing traditions, and the livelihoods of people involved in the capture, distribution, and preparation of fish as a foodstuff for humans. Furthermore, proposed limits on mercury emissions have the potential to add costly pollution controls on coal-fired utility boilers. Therefore, the methylmercury issue has attracted the attention of many levels of government (see selected external links), environmental groups, consumer advocates, science groups, food-industry-funded groups that question the science, and significant interest from electric utilities.

See also

- Dimethylmercury, mercury with a second methyl group

- Ethylmercury, a related cation

- Mercury poisoning

- Mercury regulation in the United States

- Minamata disease

- Canadian Reference Material of methylmercury

References

External links

- ATSDR - ToxFAQs: Mercury

- ATSDR - Public Health Statement: Mercury

- ATSDR - ALERT! Patterns of Metallic Mercury Exposure, 6/26/97

- ATSDR - MMG: Mercury

- ATSDR - Toxicological Profile: Mercury

- National Pollutant Inventory - Mercury and compounds Fact Sheet

- Methylmercury-in-fish exposure calculator provided by GotMercury.Org, which uses FDA mercury data with the EPA's calculated safe exposure levels.

- Methylmercury Contamination in Fish and Shellfish

- nytimes.com, Tuna Fish Stories: The Candidates Spin the Sushi

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's mercury site

- U.S. Geological Survey's mercury site

- Environment Canada's mercury site

- Health Canada's mercury site

- International Conference on Mercury as a Global Pollutant 2006-Madison, WI USA 2009-Guizhou, China 2011-Halifax, NS Canada

0 komentar :

Posting Komentar